This week, black vegan feminist blogger Aph Ko spoke on a Black Girl Nerds podcast about black veganism. As I’ve shared previously, Aph has gotten a lot of pushback, including blatantly racist remarks, for bringing attention to black vegans in an overwhelmingly white-led movement. Many white vegans don’t understand what race should have to do with veganism. Back when I was performing whiteness, I probably would have agreed with them. But now I understand the importance of this effort.

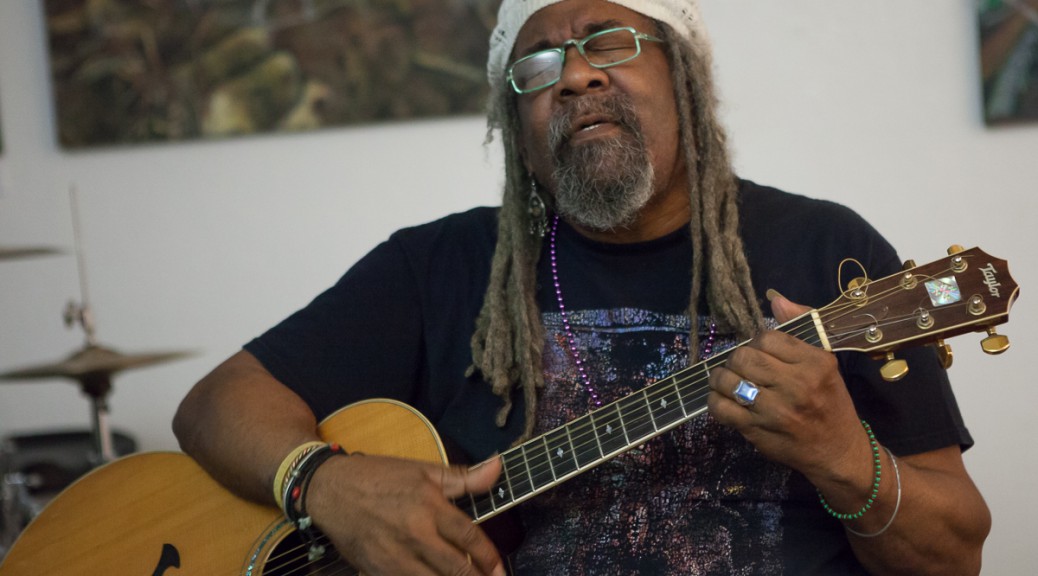

Veganism is seen by the mainstream primarily as a dietary choice for privileged people. I was reminded of this again last night, when my young nephew asked if our harvest feast (not Thanksgiving dinner) was “vegan or gluten-free.” (I was asked this question repeatedly by a fellow chorus member when I brought homemade baked goods to our rehearsals.) I explained that uncle Ziggy and I are vegan for ethical reasons, and that nothing on the dinner table contained animal products. As none of us had allergies or sensitivity to gluten, this substance was irrelevant.

On the podcast, in response to the host’s concerns about the expense of a vegan diet, Aph explained that veganism is a political choice, not a diet. She described dietary veganism as a white-centric approach, with emphasis on expensive foods that center the needs and vanity of the vegans, not the animals. She said, “I would urge people to try to change their mindsets before they try to change their economics.” Then it becomes apparent that you can meet your dietary needs with less expensive whole foods rather than pricey flesh and dairy substitutes.

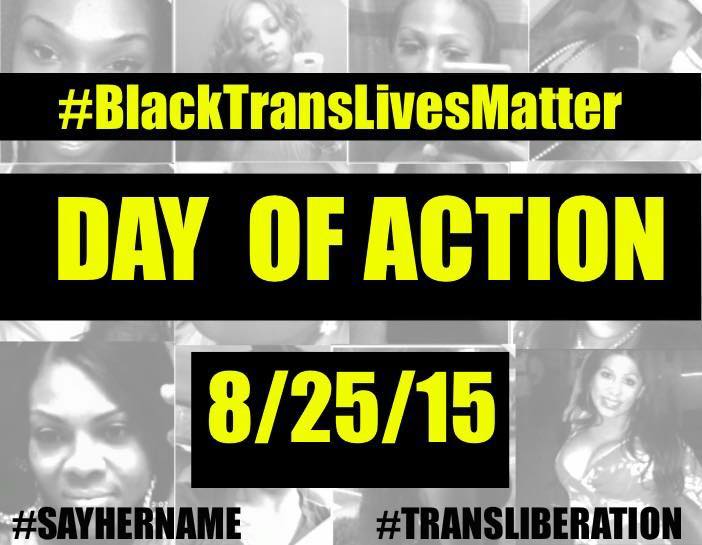

Ethical vegans aren’t immune from racism either, sadly, as Aph discussed in the podcast. Those who think that talking about black veganism is a distraction from “saving animals” really ought to check their privileges. We need to build awareness of why more black folks should be animal rights activists, and should be welcomed into the movement.

On that front, Aph is developing a new web site, Black Vegans Rock, which will debut in January. I’ll be writing more about this exciting development, so stay tuned!