[Image: A young woman lights the first of a semi-circle of thirteen candles.]

I’ve just read a moving essay by Sherry F. Colb, a Jewish vegan professor, daughter of Holocaust survivors, and author of the book Mind If I Order The Cheeseburger? (which I recommend highly). As we’re currently in the season of the High Holy Days of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I’m reflecting on my own Jewish history. As with my difficulty fitting into the black community, I’ve never felt truly at ease with this aspect of my heritage.

I was born in 1970 to a white Jewish father and a black mother who believed in God but did not profess any specific religious affiliation. My father was very secular, said he hated going to Hebrew school and so didn’t want to make me suffer through it. I did attend pre-school activities at a Jewish Community Center in Pittsburgh briefly when I was very young, before we moved to a WASP town in West Virginia in 1975.

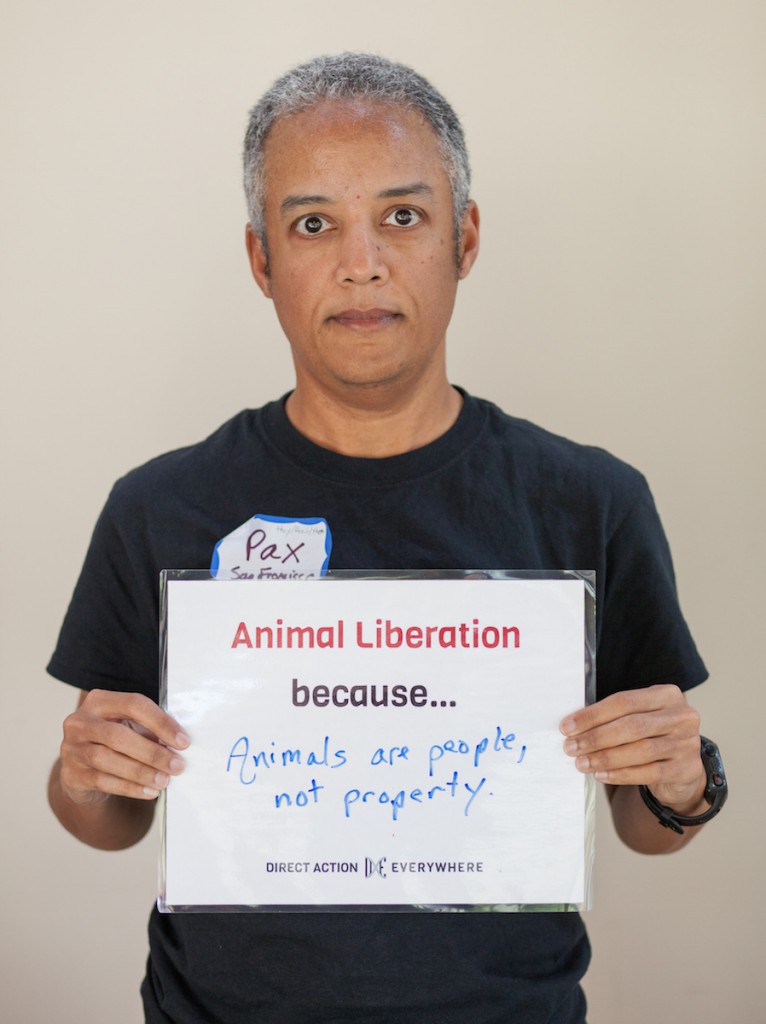

We drove to Pittsburgh to attend a Passover seder at my grandparents’ house each year, and I lit Hanukkah candles (next to our Christmas tree), but that was about the extent of my Jewish upbringing. I never had a bat mitzvah (the one pictured above is from a hired photo shoot I did a few years ago), and did not attend any religious services.

We moved back to Pittsburgh in 1982, and in 1984 I enrolled in high school in a heavily Jewish community, with numerous synagogues. We often saw Orthodox families walking to shul, and some businesses were closed on Jewish holidays. But most of my Jewish friends were secular like my father, and agnostic or atheist in their beliefs even if they did observe various holidays and customs. I had already begun to doubt the existence of God by age 12, and by age 16 I was decidedly and openly atheist, a position I haven’t wavered from since.

In college at Northwestern, I became good friends with a couple of observant Jews (of the Reform variety), one of whom I began to date seriously. He knew I was an atheist, and he hoped to become a rabbi. I tried to learn more about Judaism so that I might relate to him better, attending a few events with other students at Hillel. But I simply could not reconcile my atheism with the direct, unmistakable presence of God in the Hebrew Bible. I did not feel that I could ignore this and simply celebrate Judaism in a secular way.

I tried once again some time after moving to California in 1992, reading books about Judaism and attending High Holy Days services at a synagogue in Berkeley. Once again, I was very uncomfortable with the theism inherent in the services. I could witness these events as a cultural phenomenon, but my perspective definitely felt like that of an outsider, despite my Jewish heritage.

I knew many other atheist Jews felt strong connections to their heritage. I became quite enamored of monologist Josh Kornbluth, an atheist who spoke about Judaism frequently in his shows, and eventually traveled to the Holy Land for his bar mitzvah at the age of 52. But his upbringing – raised by Jewish Communists in New York City – was nothing like mine.

Along the way, I explored other religions. I discovered Buddhism in college, and identified as a Buddhist for a good 20 years. But I rarely practiced formal meditation, either alone or with others; Buddhism to me was (and still is, to some extent) primarily an ethical and philosophical stance. I’ve more recently read about Jainism, and have concluded that I agree with the fundamental ethics, but cannot relate to the metaphysics.

Starting in graduate school I also explored neo-paganism, doing a fair amount of reading (The Fifth Sacred Thing by Starhawk was one of my favorite books) and briefly participating in a Church of All Worlds circle. But once again, the theism – even if there was more than one god/dess – turned me off to the practice. I felt that deifying nature by assigning human characteristics to nonhuman animals, plants, and natural phenomena diminished rather than enhanced these elements of our shared Earth. I also was a vegetarian moving toward veganism by this point, and felt a disconnect from people who practiced a nature-based religion while killing and eating farmed animals. (Many of the Buddhists I met ate animal flesh as well.)

Eventually, I decided I shouldn’t try to force a connection that just wasn’t there. When I realized two years ago that I was trans, part of the reason I changed my last name along with my first was that my original last name (which I never changed through two marriages) was very obviously Jewish. While there’s nothing more wrong with Judaism than with any other theistic religion (from my perspective), I felt strongly that I wanted to assert my own identity, not my father’s.

I took the name Gethen from The Left Hand of Darkness, a book by Ursula K. Le Guin about a planet with no gender roles, as all of the humanoids are literal hermaphrodites*. Being in the family of nonbinary people makes sense to me. And yet, I haven’t felt entirely comfortable in that “tribe” either. Nonbinary people, as with trans and other gender-variant people, have widely differing attitudes and life experiences. I attended a local genderqueer peer support group briefly, but felt it only highlighted how different my feelings about gender identity and expression are from most people.

Coming out as bisexual and, later, polyamorous, predated my coming out as trans by many years, and I did actively participate in bisexual and polyamory-focused events for awhile. But eventually I stopped going to these because I realized that sexual orientation and choice to have multiple partners were not enough of a common bond for me to spend time with others on just that basis. Changing my identity from bi to queer, and becoming much less sexually active, further distanced me from these communities.

Animal rights activists are another “tribe” I’ve tried to integrate with, but I’ve found that vegans and AR activists who are also staunchly against human oppression are seriously lacking. I’ve met some good friends through Direct Action Everywhere, but I haven’t been attending actions or meetups lately, for reasons I’ve written about previously. (Edit, August 2018: I left DxE in 2015.)

Musicians are the group I’ve had the most trouble with. While I have sung or played some kind of musical instrument since the age of three, I’ve never been able to maintain connections with other musicians outside of structured, paid settings, like the band workshops I took at the Blue Bear School of Music or my singing in the Lesbian/Gay Chorus of San Francisco. I’m in an uncomfortable middle area where I’m frustrated with casual, inexperienced musicians, but not skilled enough to join the ranks of serious amateurs or professionals. The effect of testosterone on my vocal chords has further limited my ability to make music with others, though private lessons are helping.

It’s possible that I simply don’t have a “tribe,” and I should be OK with that. Over the last few months, I’ve preferred to spend as much time alone as possible, so not having any regular commitments to meet with others helps me relax a bit. But I do feel isolated and lonely at times.

I keep returning to the idea that there’s some group out there that relates to the world in the same way that I do. A community of nonbinary vegan atheist anarchists or socialists would be close to ideal, I suppose. But for now, I’ll continue to write and read and learn about the world around me, and hope that I find the inner peace I need to become a more effective activist.

* While appropriate in this fictional setting, the term “hermaphrodite” should never be used to describe humans with variant sexual anatomy. “Intersex” is the preferred term.