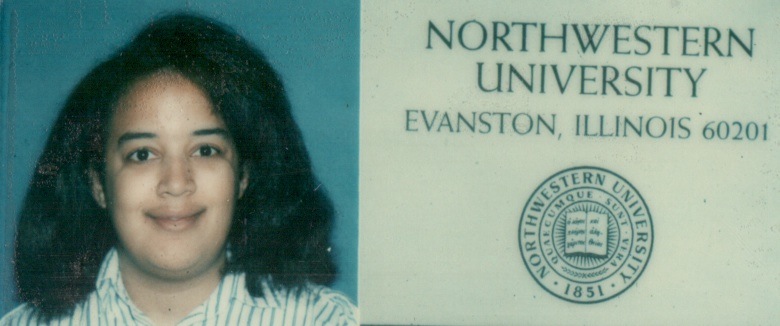

[Image: Pax’s Northwestern University student ID, circa 1990.]

There’s a meme going around on social media that’s pissing a lot of white people off. It reads:

Things white people consider to be racism

1. direct, open involvement with the KKK

2. poc saying something about white people

3. literally nothing else

The reactions are predictable.

“Is that what you think of me? I’m so hurt!”

“Not all white people are like that! Stop generalizing!”

“This is reverse racism! What if I posted something like that about black people?”

“How do you expect to get allies if you’re being so divisive? Why not speak with love and bring people together?”

I recognize these reactions because I used to say these things myself. As I posted yesterday, I come from a mixed race family (black mother, white father), and my formative years were spent surrounded by white people in a small town in West Virginia. When we moved back to the city of my birth, Pittsburgh, I was harassed by the black kids in middle school for “talking white” and not fitting in. I pushed back against that, and made mostly white friends in middle and high school.

I didn’t want to think about race. I said I was “color blind.”

When I was accepted to Northwestern University in 1988, I was excited and also hopeful that we would all be there to learn, and put race divisions behind us. I had also recently become a devotee of Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy, primarily because it resonated with me as a fellow atheist. As her followers hated the Democratic Party (which I had registered to vote with for the primaries as soon as I turned 18), but also hated the Libertarians, I felt I had no choice to re-register as Republican and vote for George H. W. Bush.

Yes, you read that correctly. I was a registered Republican and voted for George H. W. Bush in the 1988 presidential election.

So it was with this mindset that I entered college, applauding capitalism and decrying affirmative action. (Nevermind that I was a beneficiary of the latter. I reasoned that I’d earned the scholarship money thanks to my good grades, not my skin color.) Again, I made mostly white friends. I didn’t understand why black students all sat together at a table in the cafeteria, all hung out in what they informally dubbed the “black lounge,” or had a “black house” to gather in. Why all the division?

I got a position with the conservative alternate campus newspaper. I had been disturbed seeing black students with T-shirts with Malcolm X on them, holding a gun and reading “By Any Means Necessary,” and also seeing the slogan “It’s a black thing, you wouldn’t understand.” I wrote an editorial entitled “I’m black, and I still don’t understand,” spewing my vision of color-blind race unity.

In response, I was sent anonymous threatening letters, including anti-Semitic statements about my father and then-boyfriend. One envelope included an honorary membership in the KKK. Copies of these letters were sent to my mother at our home address. She was livid, and called the university to complain.

I didn’t understand the source of this anger at the time. I was truly ignorant. I doubled down even further, ignoring attempts from other black students to explain to me why my writing was so hurtful. I retreated to my studies and my supportive white friends.

By graduation, I realized that objectivism did not accurately reflect the world we live in. I moved to California for grad school at UC Berkeley – again thanks to affirmative action, this time granting me a full fellowship – and returned to my previous liberal politics. But I still made mostly white friends, and married a white man, and then another (Ziggy, my current spouse) after our divorce.

It wasn’t until many years later that I began to understand the pervasiveness of anti-black oppression and racism in this country, and the source of the anger and desire to be in spaces free from white people. Ironically, becoming an animal rights activist is what really opened my eyes to all of the oppression – against blacks and other people of color, women, LGBTQIA+, the disabled, and on and on. One book that helped me make these connections was The World Peace Diet by Will Tuttle. Given my background, it’s not surprising, though still depressing, that it took a book by a white man to clue me into these intersections.

Another turning point was reading an essay by a Chinese friend, Wayne Hsiung of Direct Action Everywhere. (Edit, Sep 2017: I left DxE in September 2015.) His essay on Performing Whiteness helped me realize why I distanced myself from other black people. Raised in a white environment with respectability politics, I really thought that it was the content of my character, not the color of my skin, that would define me to the world.

Now thanks to social media – which was not available in my younger years – I saw one black person after another beaten and killed by the police who are supposedly sworn to protect us. I saw one black trans woman after another murdered, mocked, and misgendered. I saw how the mainstream media used different words and imagery when covering blacks versus whites. And I saw black folks who spoke out against the violence being shushed, being told they were always “playing the race card” (another odious phrase I used to use myself).

I saw every cry of frustration, born of centuries of oppression at the hands of white people, met with the response of “Not all white people.”

I no longer believe in the myth of a color-blind society. I no longer believe that your skin color doesn’t matter as long as you “pull yourself up by your bootstraps.” I no longer believe all the lies and self-hatred I internalized about being black in the United States of America.

As I quoted previously from Mikael Owunna, I have gotten off the Kool-Aid of white supremacy.

So when I see a meme like the one at the top of this post, and the predictable responses, I don’t rush to reassure white people that no, of course we’re not talking about you, you’re one of the good ones. No, of course we don’t mean literally all white people. No, of course I don’t want to be divisive, we need all the allies we can get. I’ll just go back to the kitchen and be a good quiet house nigga, massa.

Fuck respectability politics.

Oh, Pax. Thank you for being brave enough to share your mistakes from the past. Of course we don’t live in a colorblind society.

I campaigned for Dukakis in 1988. I actually supported Jackson in the primary, because I saw both him and Dukakis speak, and Jackson was much more inspiring. At the time, I was working for the Democrats of the New York State Senate, and, even if I hadn’t been aware of racial issues before that, I worked with two fabulous black women, Pat and Edna, who made sure everyone around them knew and understood both racial and feminist issues. This was at the time when that whole horrible thing happened with Tawana Brawley, and Rev. Sharpton was coming upstate from the city with attorneys Maddox and Mason.

I’m sorry those children were so cruel to you. It seems this goes right back to what I’ve been saying about the pain of being considered not black/white/Jewish/queer/trans/cis enough. I wish you could have known Pat and Edna at that time.

I voted for Dukakis in the primary myself. I didn’t support Jackson because of his religious affiliation.

I think I would feel the same way about Jackson now that you did, then, but the contrast between his speech and Dukakis’ was just glaring. I got caught up in the excitement. This was back when you could see a presidential candidate without paying at least $200… I got to see Gore free, too, in 1984.

Thanks for writing this.